Hey look! OAuth is getting spiffed up a bit. The original OAuth 2.0 specification was released in October 2012 as RFC 6749. It replaced OAuth 1.0, released in April 2010. There have been some extensions over the years. A new OAuth specification has been proposed and is currently under discussion. As of this blog post’s writing, the specification was most recently updated on March 8, 2020. If approved, OAuth 2.1 will obsolete certain parts of Oauth 2.0 and mandate additional security best practices. The rest of the OAuth 2.0 specification will be retained.

This post assumes you are a developer or have similar technical experience. It also assumes you are familiar with OAuth and the terms used in the various RFCs. If you’d like an introduction to OAuth and why you’d consider using it, Wikipedia is a good place to start. This post discusses proposed changes to OAuth that might affect you if you are using OAuth in your application or if you implement the OAuth specification.

Why OAuth 2.1?

It’s been a long time since OAuth 2.0 was released. A consolidation point release was in order. As outlined in a blog post by Aaron Parecki, one of the authors of the OAuth 2.1 draft specification:

My main goal with OAuth 2.1 is to capture the current best practices in OAuth 2.0 as well as its well-established extensions under a single name. That also means specifically that this effort will not define any new behavior itself, it is just to capture behavior defined in other specs. It also won’t include anything considered experimental or still in progress.

So, this is not a scrape and rebuild of OAuth 2.0. Instead, OAuth 2.1 consolidates the changes and tweaks to OAuth 2.0 that have been made over the past eight years, with a focus on better default security. It establishes the best practices and will serve as a reference document. Here’s a suggested description pulled from the ongoing mailing list discussion: “By design, [OAuth 2.1] does not introduce any new features to what already exists in the OAuth 2.0 specifications being replaced.” Many of the new draft specification details are drawn from the OAuth 2.0 Security Best Current Practices document. However, in the name of security best practices, some of the more problematic grants will be removed.

At the end of the day, the goal is to have a single document detailing how to best implement and use OAuth, as both a client and an implementor. No longer will developers have to hunt across multiple RFCs and standards documents to understand how a specified behavior should be implemented or used.

I use OAuth in my application, what does OAuth 2.1 mean to me?

Don’t panic.

As mentioned above, the discussion process around this specification is ongoing. A draft RFC was posted to the IETF mailing list in mid-March. As of the time of writing, the revision and discussion are still actively occurring.

You may ask, when will it be available? The short answer is “no one knows”.

The long answer is “truly, no one knows. It does seem like we’re early in the process, though.”

Even after OAuth 2.1 is released, it will likely be some time before it is widely implemented. Omitted grants may be supported with warnings forever. The exact changes to the specification are still up in the air, the release of the RFC is even further in the future and when it is released, you can continue to use an OAuth 2.0 server if that serves your needs.

That said, when this is released the biggest impact on people who use OAuth for authentication or authorization in their applications will be planning on how to handle the removed grants: the Implicit grant or Resource Owner Password Credentials grant.

What is changing?

The draft RFC has a section outlining the major changes between OAuth 2.0 and OAuth 2.1. There may be other changes not captured there but the goal is to document all formal changes there. There are six such changes:

The authorization code grant is extended with the functionality from PKCE (RFC7636) such that the only method of using the authorization code grant according to this specification requires the addition of the PKCE mechanism

Redirect URIs must be compared using exact string matching as per Section 4.1.3 of OAuth 2.0 Security Best Current Practices

The Implicit grant (“response_type=token”) is omitted from this specification as per Section 2.1.2 of OAuth 2.0 Security Best Current Practices

The Resource Owner Password Credentials grant is omitted from this specification as per Section 2.4 of OAuth 2.0 Security Best Current Practices

Bearer token usage omits the use of bearer tokens in the query string of URIs as per Section 4.3.2 of OAuth 2.0 Security Best Current Practices

Refresh tokens must either be sender-constrained or one-time use as per Section 4.12.2 of OAuth 2.0 Security Best Current Practices

Whew, that’s a lot of jargon. We’ll examine each of these in turn. But before we do, let’s define a few terms that will be used in the rest of this post.

- A

clientis a piece of code that the user is interacting with; browsers, native apps or single-page applications are all clients. - An

OAuth serverimplements OAuth specifications and has or can obtain information about which resources are available to clients—in the RFCs this is called an Authorization Server, but this is also known as an Identity Provider. Most users call it “the place I log in”. - An

application serverdoesn’t have any authentication functionality but knows how to delegate to an OAuth server. It has a client id which allows the OAuth server to identify it.

The Authorization Code grant and PKCE

The authorization code grant is extended with the functionality from PKCE (RFC7636) such that the only method of using the authorization code grant according to this specification requires the addition of the PKCE mechanism

Wow, that’s a mouthful. Let’s break that down. The Authorization Code grant is one of the most common OAuth grants and is the most secure. If flow charts are your jam, here’s a post explaining the Authorization Code grant.

The Proof Key for Code Exchange (PKCE) RFC was published in 2015 and extends the Authorization Code grant to protect from an attack if part of the authorization flow happens over a non TLS connection. For example, between components of a native application. This attack could also happen if TLS has a vulnerability or if router firmware has been compromised and is spoofing DNS or downgrading from TLS to HTTP. PKCE requires an additional one-time code to be sent to the OAuth server. This is used to validate the request has not been intercepted or modified.

The OAuth 2.1 draft specification requires that the PKCE challenge must be used with every Authorization Code grant, protecting against the authorization code being hijacked by an attacker.

Redirect URIs must be compared using exact string matching

Redirect URIs must be compared using exact string matching as per Section 4.1.3 of OAuth 2.0 Security Best Current Practices

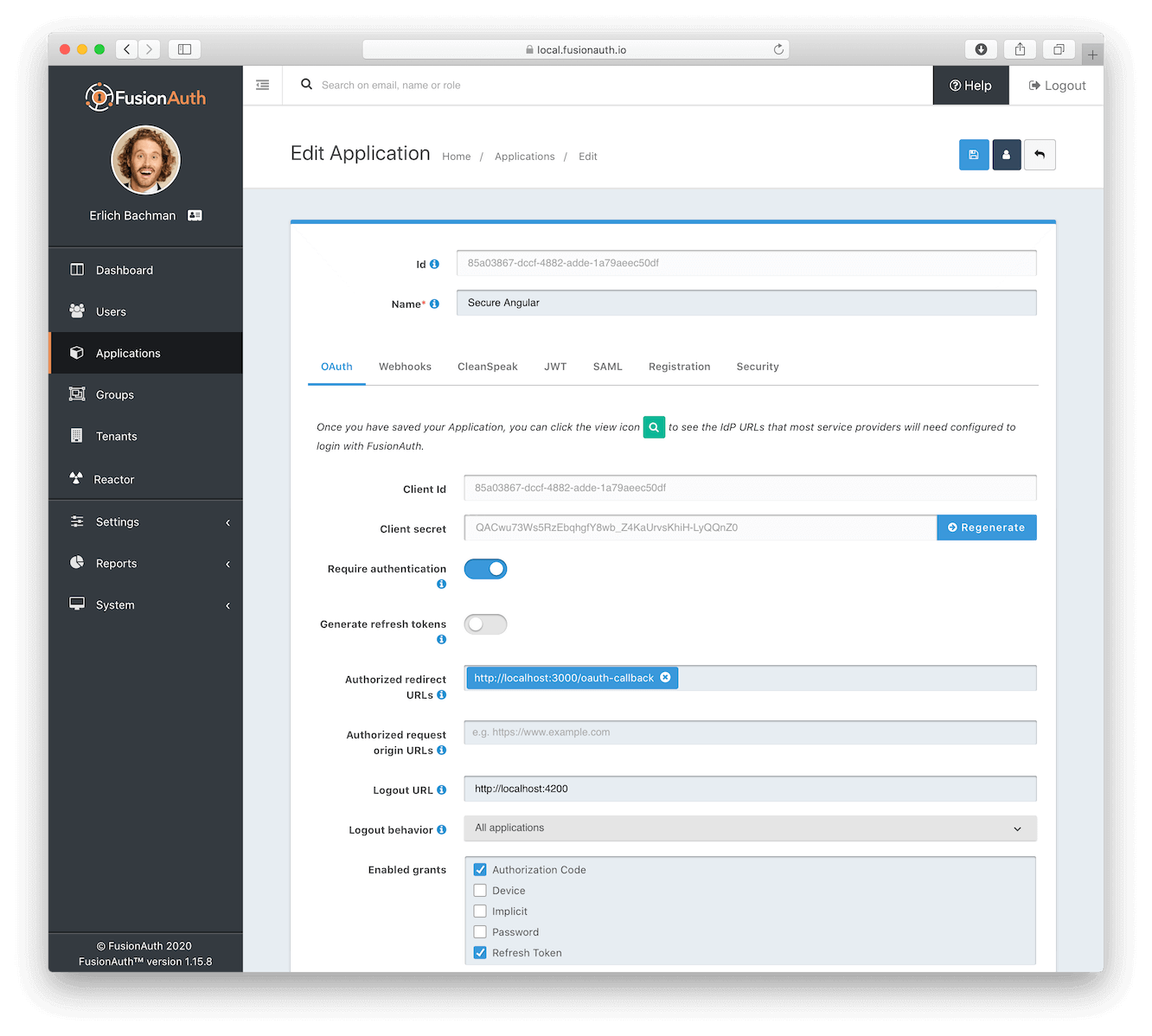

Some OAuth grants, notably the Authorization Code grant, use a redirect URI to determine where to send the client after success. For example, here’s a FusionAuth screen where the allowed redirect URIs are configured (it is the “Authorized redirect URLs” setting):

In this case, the only allowed value is http://localhost:3000/oauth-callback but you can configure multiple values. The client specifies which one of these the user who is signing in should be redirected to.

Now, it would sure be convenient to support wildcards in this redirect URI list. At FusionAuth, we hear this request from folks who want to simplify their development or CI environments. Every time a new server is spun up, the redirect URI configuration must be updated to include the new URI.

For example, if a CI system builds an application for every feature branch, it might have the hostname dans-sample-application-1551.herokuapp.com, if the feature branch was a fix for bug #1551. If I wanted to login using the Authorization Code grant, I’d have to update the redirect URI settings for my OAuth server to include that specific redirect URI: https://dans-sample-application-1551.herokuapp.com/oauth-callback.

And then when the next feature branch build happened, say for bug #1552, I’d have to add https://dans-sample-application-1552.herokuapp.com/oauth-callback and so on. Obviously, it’d be easier to set the redirect URI to a wildcard value like https://dans-sample-application-*.herokuapp.com/oauth-callback; in an ideal world, any URL matching that pattern would be acceptable to the OAuth server. Of course, if you are using FusionAuth, you can update your application configuration as part of the CI build process as an alternative.

An additional use case for a wild card redirect URI is when the redirect URI needs dynamic parameters useful to the final destination page, like trackingparam=123&specialoffer=abc. These may be appended to the redirect URL before the OAuth process began. A URL with dynamic parameters won’t match any of the configured redirect URIs, and so the redirect fails.

However, allowing such wildcard matching for the redirect URI is a security risk. If the redirect URI matching is flexible, an attacker could redirect a user to an open redirect server controlled by them, and then on to a malicious destination; OWASP further discusses the perils of such open redirect servers. While this would require compromising the request in some fashion, using exact matching for redirect URIs eliminates this risk because the redirect URI is always a known value.

The Implicit grant is removed

The Implicit grant (“response_type=token”) is omitted from this specification as per Section 2.1.2 of OAuth 2.0 Security Best Current Practices

The Implicit grant is inherently insecure when used in a single-page application (SPA). If you use this grant, your access token is exposed. You’ll get an access token that is either in the URL fragment, and accessible to any JavaScript running on the page, or is stored in localstorage and is accessible to any JavaScript running on the page, or is in a non HttpOnly cookie, and accessible to any JavaScript running on the page. (Is there an echo in here?) In all cases, an attacker gaining an access token is allowed to, well, access resources as your end user. Bad.

Access tokens are not necessarily one-time use, and can live from minutes to days depending on your configuration. So if they are stolen, the resources they protect are no longer secure. You may think “well, I don’t have any malicious JavaScript on my site.” Have you audited all your code, and its dependencies, and their dependencies, and their dependencies? (There’s that echo again.) Do you audit all your code automatically? Extensive dependency trees can lead to unforeseen security issues: someone took over an open source node library and added malicious code that was downloaded millions of times.

Here’s an article about the least insecure way to use the Implicit grant for an SPA. This redirects to the SPA after setting an HttpOnly cookie. In the end it basically recreates the Authorization Code grant, illustrating how the Implicit grant can’t be made secure.

The OAuth 2.1 draft specification omits the Implicit grant. The “OAuth 2.0 Security Best Current Practices” document, however, stops short of prohibiting the Implicit grant, stating instead:

In order to avoid these issues, clients SHOULD NOT use the implicit grant (response type “token”) … unless the unless access token injection in the authorization response is prevented and the aforementioned token leakage vectors are [mitigated]

From my perspective, this means that the omission of this grant in the final RFC is still not a done deal. However, if the final version of the OAuth 2.1 spec omits the Implicit grant, a compliant OAuth 2.1 server will not support it. If you use this grant in your application, you’ll have to replace it with a different one if you want to be compliant with OAuth 2.1. May we suggest the Authorization Code grant?

The Resource Owner Password Credentials grant is removed

The Resource Owner Password Credentials grant is omitted from this specification as per Section 2.4 of OAuth 2.0 Security Best Current Practices

This grant was added to the OAuth 2.0 specification with an eye toward making migration to OAuth compliant servers easier. In this grant, the application server receives the username and password (or other credentials) and passes it on to the OAuth server. Here’s an article breaking down each step of the Resource Owner Password Credentials grant. This grant is often used for mobile applications. While this grant made it easier to migrate OAuth with minimal application changes, it breaks the core delegation pattern and makes the OAuth flow less secure. No longer can you leave the work of securing your user’s credentials and data up to the OAuth server so you can focus on building your own app. Now you must ensure that your application backend is just as secure, since it will also be sent the username and passwords.

Unlike the Implicit grant, the “OAuth 2.0 Security Best Current Practices” document requires that this grant no longer be allowed:

The resource owner password credentials grant MUST NOT be used.

So it’s a good bet that this grant is going to be omitted in the final RFC. If you have a mobile application using this grant, you can either update the client to use an Authorization Code grant using PKCE or keep using your OAuth 2.0 compliant system.

No bearer tokens in the query string

Bearer token usage omits the use of bearer tokens in the query string of URIs as per Section 4.3.2 of OAuth 2.0 Security Best Current Practices

Bearer tokens, also known as access tokens, allow access to protected resources and therefore must be secured. These days, most tokens are JWTs. Clients store them securely and then use them to make API calls back to the application server. The Application server then uses the token to identify the user calling the API. When first defined in RFC 6750, such tokens were allowed in headers, POST bodies or query strings. The draft OAuth 2.1 spec prohibits the bearer token from being sent in a query string. This is a particular issue with the Implicit grant (which is omitted from the OAuth 2.1 specification).

A query string and, more generally, any data in the URL, is never private. JavaScript executing on a page can access it. A URL or components thereof may be captured in server log files, caches, or browser history. In general, if you want to pass information privately over the internet, use TLS and put the sensitive information in a POST body or HTTP header.

Limiting refresh tokens

Refresh tokens must either be sender-constrained or one-time use as per Section 4.12.2 of OAuth 2.0 Security Best Current Practices

Refresh tokens allow a client to retrieve new access tokens without reauthentication. This is helpful if you need access to a resource for longer than an access token live, or if you need infrequent access (such as being logged into your email for months or years). As such, they are typically longer lived than access tokens. Therefore you should take twice as much care when it comes to securing a refresh token.

If they are acquired by an attacker, the attacker can create access tokens at will. Obviously at that point, the resource which the access tokens protect will no longer be secure. As an example of how to secure refresh tokens, here’s a post using the Authorization Code grant which stores refresh tokens securely using HttpOnly cookies and a limited cookie domain. Incidentally, never share your refresh tokens between different devices.

The OAuth 2.1 draft specification provides two options for refresh tokens: they can be one-time use or tied to the sender with a cryptographic binding.

One time use means that after a refresh token (call it refresh token A) is used to retrieve an access token, it becomes invalid. Of course, the OAuth server can send a new refresh token (call it refresh token B) along with the requested access token. In this case, once the newly delivered access token expires, the client can request another access token using refresh token B, receive the new access token and a new refresh token C, and so on and so on. The change to one-time use refresh tokens may require changing client code to store the new refresh token on every refresh.

The other recommended option is to ensure the OAuth server cryptographically binds the refresh token to the client. The options mentioned in the “OAuth 2.0 Security Best Current Practices” document are OAuth token binding or Mutual TLS authentication RFC 8705. This binding ensures the request came from the client to which the refresh token was issued.

To sum up, the OAuth 2.1 spec requires an OAuth server protect refresh tokens by requiring them to either be one-time use or by using cryptographic proof of client association.

What’s unchanged?

These are the major changes in the proposed OAuth 2.1 RFC. The OAuth 2.1 spec is built on the foundation of the OAuth 2.0 spec and inherits all behavior not explicitly omitted or changed. For example, the Client Credentials grant, often used for server to server authentication, continues to be available.

Can you use OAuth 2.1 right now?

Well no. As of right now, there’s nothing stamped “OAuth 2.1”. And the draft spec isn’t finalized. But if you follow best practices around security, you can reap the benefits of this consolidated draft, and prepare your applications for when it is released. FusionAuth has an eye toward the future and already has support for many of these changes.

When writing a client application, avoid the Implicit grant and the Resource Owner Password Credentials grant. However, as these are part of the OAuth 2.0 specification, they are currently supported by FusionAuth.

Make sure your OAuth server is doing to following:

- Using PKCE whenever you use the Authorization Code grant. (FusionAuth highly recommends using PKCE.)

- Make sure that your redirect URIs are compared using exact string matches, not wildcard or substring matching. (FusionAuth has you covered: “URLs that are not authorized [configured in the application] may not be utilized in the redirect_uri”.)

- Make sure bearer tokens are never present in the query string. (FusionAuth doesn’t support access tokens in the query string other than in the Implicit Grant. But you shouldn’t be using that anyway.)

- Limit your refresh tokens to make sure they are not abused. (FusionAuth forces refresh tokens be tied to the client to which the refresh token was sent, but doesn’t, as of now, follow the cryptographic signing behavior outlined in the OAuth 2.1 draft.)

Future directions

It’s tough to make predictions, especially about the future.” - Yogi Berra

Please note that this specification is under active discussion on the OAuth mailing list. If you are interested in following or influencing this RFC, review the discussion archives and/or join the mailing list.

Beyond this draft RFC, which is going to consolidate security best practices but leave most of OAuth 2.0 untouched, there’s also an OAuth3 working group, reimagining the protocol from the ground up. The OAuth3 specification is further from release than the OAuth 2.1 specification.